Forget spark plugs, start

your car with nanotubes

19 November 2005 · From

New Scientist Print Edition. Subscribe and get 4 free

issues. Celeste Biever

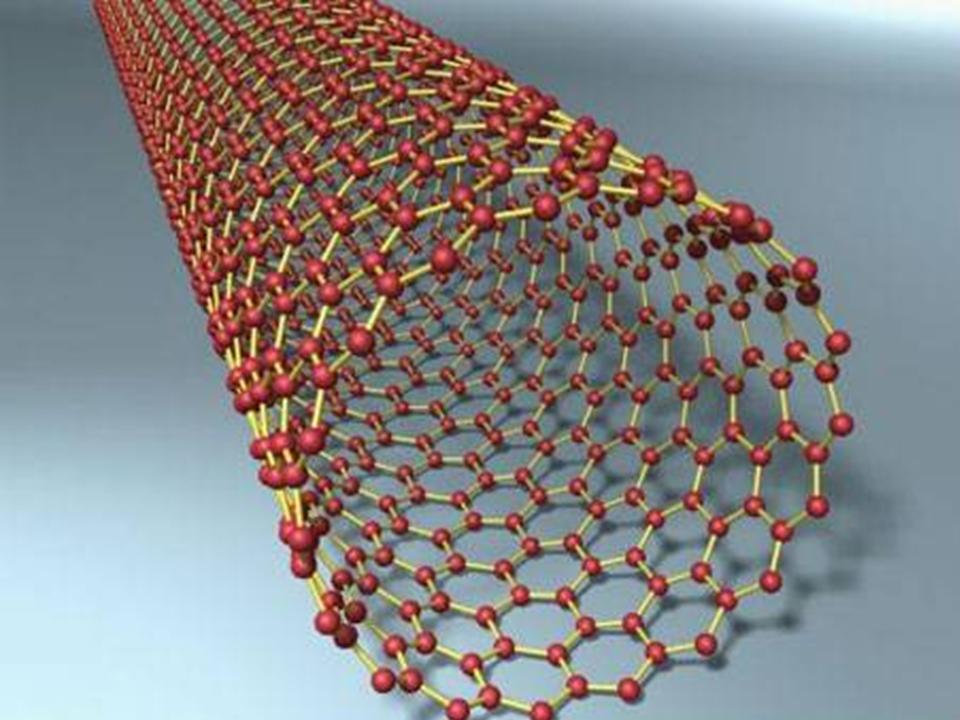

THE accidental discovery

that carbon nanotubes can be set alight with nothing more

than a bright light could lead to a more efficient way of

igniting car and rocket fuel.

Three years ago, a

student working in Pulickel Ajayan's lab at Rensselaer

Polytechnic Institute in New York inadvertently ignited the

pile of carbon nanotubes he was photographing (New

Scientist, 4 May 2002, p 27). Researchers think that the

nanotubes ignite because they absorb light more efficiently

than they can dissipate the energy as heat. The phenomenon

only happens when iron impurities are present, although the

exact process is uncertain.

Despite the mechanism's

mystery, researchers are already beginning to exploit the

effect. Bruce Chehroudi and

Stephen Danczyk of the US Air Force Research Laboratory at

Edwards air force base in California have found that

nanotubes placed one millimetre away from a droplet of

methanol or a liquid rocket fuel called RP-1 can ignite the

droplet when flashed with light. They think the burning

nanotubes ignite the vapour around the droplet, which then

ignites the fuel.

The pair have also

ignited solid firework propellants such as potassium

chlorate, simply by placing the nanotubes on top of them.

Encouraged by this success, they have filed patents on

nanotube ignition systems for car and rocket fuels. Standard

petrol engines rely on a spark produced by a high voltage

between two electrodes at the tip of the spark plug. This

ignites an atomised mixture of fuel and air in a combustion

chamber, and the expanding gas drives a piston. But sparking

does not burn all the fuel, creating inefficiency and

pollution. The wasted fuel drips into the exhaust pipe, from

where it is released into the atmosphere. And if rocket fuel

fails to ignite, the mixture of oxygen and hydrogen can

build up and ignite later in an explosion that can damage

the rocket.

Nanotubes could prevent

this by providing "distributed ignition" through the bulk of

a fuel, with no single point of failure. The nanotubes would

be blasted into the fuel as it is atomised, and mixed with

the air inside the cylinder. A flash of light from a bright

LED would ignite the nanotubes, and hundreds of tiny flames

would then ignite the fuel throughout, doing away with the

spark plug. "If one nanotube fails, you have lots of

others," says Chehroudi.

"Igniting at multiple points has always been a dream."

"A flash of light ignites

the nanotubes, which then ignite the fuel throughout"

The ignition system would

be more efficient because the nanotubes' dispersion

throughout the fuel mixture means that the heat produced is

used all at once to drive the piston, rather than gradually,

so there is less heat loss. In addition, all the fuel would

be burnt. This increased efficiency could justify the cost

of the new engines that would be needed, says the team. The

researchers are now trying to find which light wavelengths

and intensities work best. The idea is also being

investigated as a more reliable wire-free way of setting off

explosive bolts for rocket-stage separation, says Riad Manaa

at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California.

Wires often degrade and fail under high mission temperatures

and pressures: an optical fiber might do the job better.

From issue 2526 of New

Scientist magazine, 19 November 2005, page 30

OTHER APPLICATIONS:

NANOTUBE (FLASH) IGNITION

Back

to Top of This Page

NOTE:

Contact Advanced Technology Consultants for

consulting needs and opportunities in this area